Card 1

Card 1 Card 2

Card 2

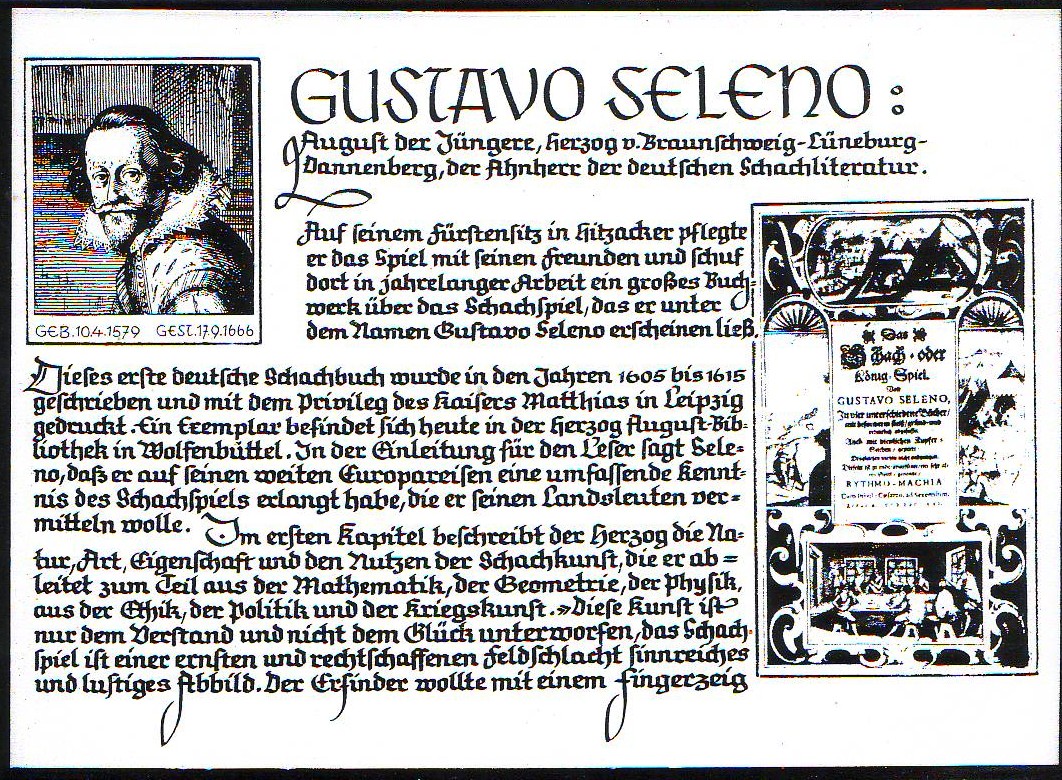

In 1616, Gustavo Seleno, the pen-name of Augustus, the Duke of Brunswick (1579-1666), a learned aristocrat who published his Bucher von Schach und Königs-Spiel (Liepzig, 1616). The book is noteworthy as the first chess book written in German, for its commentary on the King’s Gambit, and for its account of Living Chess in the village of Stroebeck, where chess was taught in the village school’s curriculum. An English translation was offered by Sarratt (London, 1817).

Several years ago, I acquired these two old postcards printed in Germany. I asked my chess friend Eric Gavdreau, who lived for many years in Germany, to translate it from old German into French.

I recently asked another of my friends, John Bleau, a professional translator, to provide an English translation.

I offer these scans and translations as a Christmas gift to the readers of the Chesstamp Review.

Card 1

Card 1

Card 2

Card 2

Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lünenburg, father of German chess literature.

At his dukedom at Hitzacker, he applied himself to chess with his friends and laboured for years on a great literary work on the royal game which he published under the pseudonym Gustavo Selano.

This, the earliest book on chess, was written during the years between 1605 and 1615, and with the support of Emperor Matthias, was printed in Leipzig. There is today a copy in the Duke Augustus library in Wolfenbúttel. In the reader’s forward, Selano said that he wished to share the extensive knowledge he had acquired about chess during his distant travels throughout Europe.

In the first chapter, the Duke describes the nature, method, character, and goal of the art of chess that he found comparable to math, geometry, physics, ethics, politics, and martial arts. “This art is entire subject to the intelligence and not at all to chance: chess is a faithful and humorous model of serious and fair combat. Its inventor wished to explain that the power of the majesty of a duke cannot survive without the support and help of his subjects, that he can easily be beaten by strangers and enemies if he is not loyally protected by his own people.”

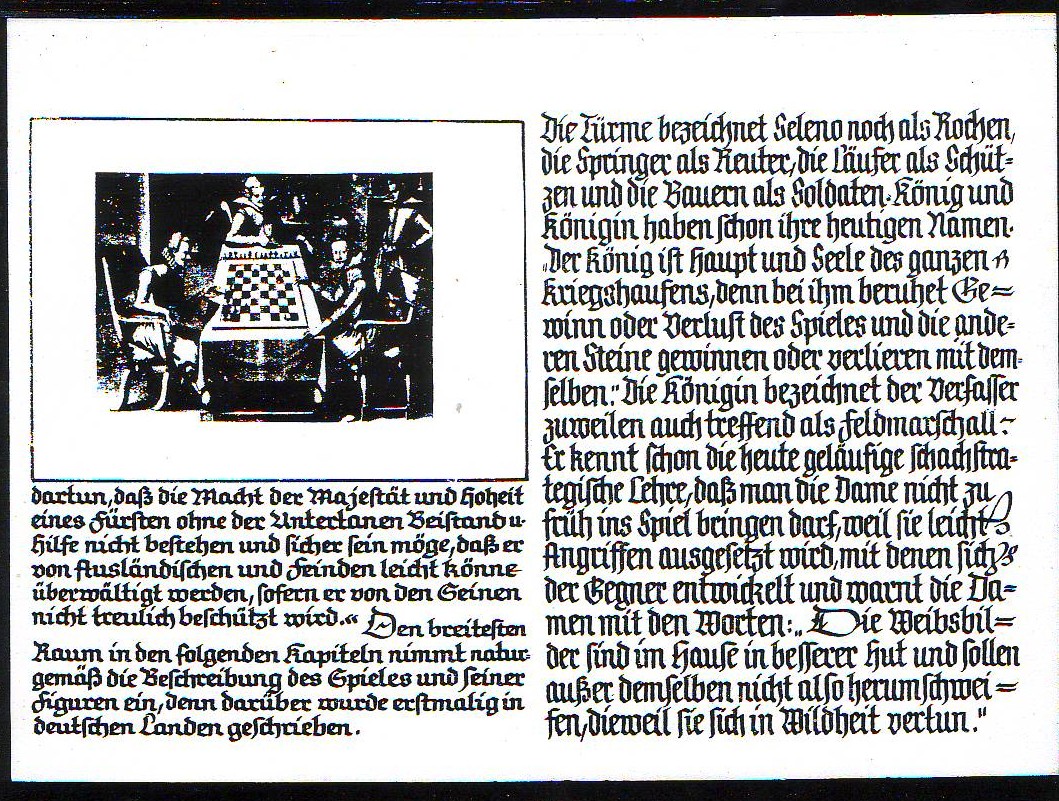

Naturally, the description of the game itself and its pieces becomes more prominent in the following chapters, as this was the first time that anyone wrote on this subject in a Germanic country.

Selena called the rooks “Kochen*,” the knights “Reuter*,” and the bishops “marksman” and the pawns “soldiers.” The names King and Queen have remained the same through time. “The King is the head and soul of this entire heap of warfare and he is where victory and defeat are decided; the other pieces win or lose with him.” The author rightly calls the queen the army’s Field Marshall. He is already familiar with strategic chess teachings such as the proscription against bring the queen out too early, since this exposes her too soon to attacks that accelerate the opponent’s development, and he admonishes that “Women are best protected at home, and besides, they should not stray outdoors, as they may find perdition in the wilderness.”

*old German words whose meaning is unknown to me.